I really like that.

|

“’We hoped for this but didn’t expect it,’ said one, Roman Dakus. Mr. Dakus had been in Kiev at Independence Square, or Madian as it is known here, off and on for three months, he said. ‘It was very, very difficult to stay on the square in the cold at night. But we warmed one another with our hearts and our souls. People really changed their mind-set because of these events,’ Mr Dakus added. ‘Before people thought, “Nothing really depends on me.” They preferred to say that and to think like that. But after this situation, they think differently. They believe in their struggle when they are all together.’” (NYT Sun Feb, 23, 2014 pg. 11)

I really like that.

0 Comments

Yes, a letter, though it was an email of course. Somehow "email" seems too lightweight, unable to carry enough substance to connote meaning. The letter is to Phil Rosenthal, copying Gail MarksJarvis, two longtime journalists at the Tribune. It is an attempt at responsive virtuosity regarding their February 5, 2014 columns that jointly appeared under the headline, "Shivers on Wall Street". I have written each before, have heard back from Gail, but as yet, not from Phil. You can read Phil's column here and Gail's here. You know how you can tell when folks are good people from what they say, do, write?...you can feel it. Both Phil and Gail are good people and I wish them the best. February 5, 2014 Hi Phil, Enjoyed your column today (Shivers on Wall St, Trib Bus. 2/5/14)—especially appreciated that you stated flatly, “The market is a barometer of corporate health, not the fiscal health of the population as a whole.” Indeed, since 10% of the population own somewhere in excess of 80% of all stocks, bonds and mutual funds (EPI, State of Working America 2011), this is surely a topic crying out for more discussion. This question of representation has important, and reverberating consequences. Of course you repeat the shibboleth about long-term investing, urging investors to hold on despite the turmoil. This is in some sense true, until it’s not. If the market represents only a small fraction of the public, one wonders when the rest of us will object strenuously to such self-serving fetishization, especially as many find themselves in difficult economic straits. And of course, as Keynes said, “In the long run we’re all dead” anyway. Which I think is a process that is hastening, your citing of University of Chicago professor Eugene Fama’s Nobel Prize winning work is a tell. Fama is a neoliberal economist—his work captured the central principal of that specious secular religion by “advancing the theory”, as you say, that “markets take into account all available information at all times.” Fortunately you limit the reach of this assertion with your barometer comment above, and by quoting Tyson, the investing author who says “there is a disconnect” between the market recovery and the well-being of folks generally. These empirical and generally empathic responses to theory are yours and Tyson’s. Neoliberals do in fact believe that the market is the sum total of all information—not just about the market, but about everything, literally. There is no disconnect. A group of colleagues and I recently watched a lecture given by Phillip Mirowski, a philosopher of economics at Notre Dame University in which he sketched out the difference between neoclassical and neoliberal economics and how we have moved from the former to the latter and the frightening ramifications of that movement. Here’s my blog post, which includes the lecture, introducing the talk on DePaul’s Institute for Nation and Culture online journal: http://environmentalcritique.wordpress.com/2013/12/10/is-the-market-a-hyperobject/ I encourage you to take the time to watch the lecture; Mirowski is a prolific author and highly regarded. It’s not a comforting picture, especially when you take into account the power of these true believers whose conviction rivals that of true believers anywhere. By way of comment, perhaps prematurely, any substantive reflection upon this “true belief” reveals that it is utter nonsense and must be a product of either hubris or idiocy, or perhaps both, Nobel Prize or not. (Or perhaps some very particular motivation/proclivity, which I think, would likely include measures of the aforementioned). Economics is about as self-referential as anything we do—it can only stand for itself, its precepts. In all cases representation is always just that: a singular, even myopic picture of something; and there are as many pictures as there are picture-takers. Unless, of course, a singular picture becomes everything. That, succinctly, is what seems to be happening. In the opening pages of his Simulations (1981) Baudrillard observes, “It is a generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it…[I]t is with this same imperialism that present-day simulators attempt to make the real, all of the real, coincide with their models of simulation. But is it no longer a question of either maps or territories. Something has disappeared: the sovereign difference, between the one and the other, that constituted the charm of the abstraction. Because it is difference that constitutes the poetry of the map and the charm of the territory, the magic of the concept and the charm of the real.” [1] (Emphasis mine) For neoliberals markets are the real—Fama "proved it"--the entire exercise a practical tautology since it is self-referential--and won the Nobel Prize. Metaphysics, epistemology and ontology, the problems of philosophy all solved. The mapmakers make the map and the real “does not survive it...”. Yet disregarded all along is that everything takes place in a context; everything relies on assumptions taken. Thus neoliberals go round and round in a dance of self-referential surety.

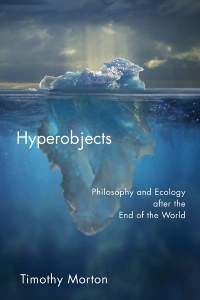

This fits well with an earlier note to you in which I encouraged you to explore privacy and data collection more deeply, citing the work of UPenn professor Joseph Turow and reporting done by NYT writers Charles Duhigg and Natasha Singer. [2] The collection, processing and returning of data to the public in the form of tangibles and intangibles is the manufacturing process of a simulacrum—and that process is becoming ever more efficient—driven by the true believers in that specious secular religion, who again, are sure they can count (represent) everything. After all, what is a market, as it has come to be defined, but data? The mapmakers make the map. Flesh and blood people, who not only have the “charm of the real”, but its suffering as well, are not accounted for in the models. But you feel them Phil; so does Tyson, and so do most of us, however bewitched by neoliberalism we are—and we are bewitched. Yet reality, in some form, has a way of upsetting abstractions. The headline for Gail MarksJarvis’ companion piece asks, “Tough year ahead or necessary correction?” My guess is both. Best to you (and to you Gail), EJTangel Chicago [1] Jean Baudrillard, Simulations (1981) PDF. For more on Baudrialld see Jean Baudrillard, Selected Writings, Edited and Introduced by Mark Poster (University of California Irvine professor of History, Film and Media Studies) [2] Articles are posted under the rubric Divide, Shape and Profit, about halfway down the page. repost from Ecology Without Nature... My Talk to the Rice Faculty in mid-Feb Posted: 08 Feb 2014 10:20 AM PST The Humanities in the Age of Ecological Emergency Timothy Morton Humans created the Anthropocene, with its global warming. Not jellyfish. Not fungi. Not coral reefs. The Humanities know a thing or two about humans. It is imperative therefore that the Humanities be in the mix of thinking that addresses the Anthropocene. Not as a decorative adjunct to science, but alongside it, fueling it, thinking it, analyzing and critiquing it. This talk is about that. And, I would add, the Humanities need to be ante-capital, as in before, so we can get a clear fix on what we are actually doing. Tim Morton is professor of English at Rice University, author of Hyperobjects (2013), Realistic Magic (2013) and The Ecological Thought (2010) and more. A wiki bio here. My favorite quote (thus far) is, "Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear." (Hyperobjects) EJT |

Archives

February 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed